This is more of a ‘That Is Not How Spiders Work’ post than a lifecycle rework, since I probably am not going to be making a full life cycle for my L. tarantula model (mostly because I can’t currently think of how to do the spiderlings). But wolf spiders are cool, so let’s get into them.

First, the spider model here is not a tarantula in the way most people are going to think about them. Tarantulas are mygalomorph spiders (in the infraorder Mygalomorphae – spider taxonomy is complicated), and are more closely related to trapdoor spiders and funnelwebs than most of the spiders we typically see in the UK. We have one native mygalomorph spider, the Purseweb spider, and it is tiny and cute.

This model is clearly based on Lycosa tarantula, which is more commonly known now as the tarantula wolf spider. It is where the name for tarantulas came from, probably because it is a pretty big spider, so when Europeans encountered other Big Spiders, the shorthand stuck around.

Okay, so it’s not a tarantula-tarantula. Is it a reasonable wolf spider life cycle? Also no.

Spiders are actually really good parents, for invertebrates. Eggs are not laid in a heap, but encased in a protective silk egg sac. These can be really complicated – some have extra materials woven in, some use several different types of silk, they are waterproof, insulating etc – and in many species the female spider will carry the egg sac around with her to protect it. She may transport the spiderlings around after they have hatched, provide them with food (or even feed the babies with herself), and protect the delicate early molts.

Wolf spiders carry their egg sac at the back, clutched in their spinnerets, and will aid the young in breaking out of the egg sac once they hatch. They are very protective of the eggs and will search for them if they are dropped (occasionally accidentally attaching other Egg Sac Sized Things instead). They definitely do NOT plonk a loose heap of eggs in the middle of an orb web (most wolf spiders do not make webs at all – they are active hunters!).

I could attach a pale blob for an egg sac to the back of my spider model (left: blu tack), but the abdomen doesn’t really bend up enough. Real spiders have a very narrow pedicel linking their cephalothorax (front bit) and abdomen, which gives them fantastic waist flexibility for aiming silk / holding things without impeding movement too badly.

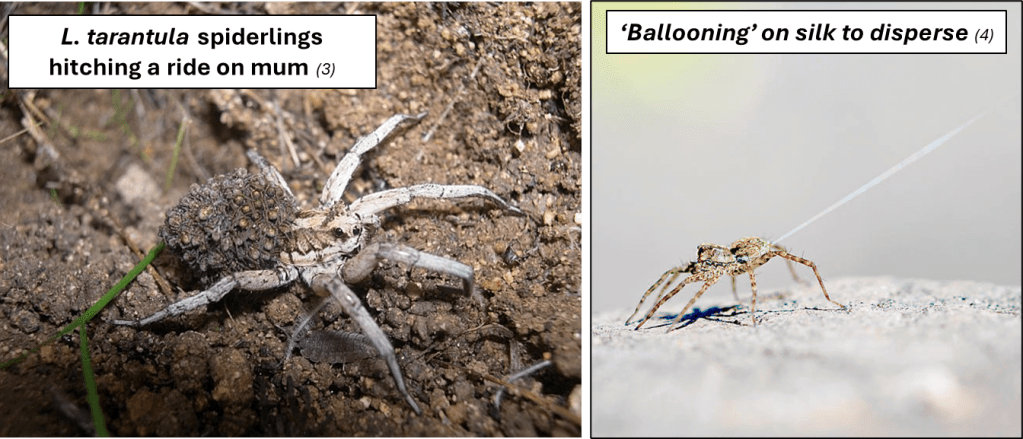

The pile of loose spiderlings isn’t terrible, but it isn’t now wolf spiders go about their nursery work either. Once the spiderlings have hatched, they will climb up onto the mother’s back and ride around on her for a while, protected, until they drop off to disperse on foot – or via ‘ballooning’. This is when a tiny spider throws a line of silk up into the air, and the combination of wind and electrostatic interactions between the silk & air will lift the spider up and away! This is really important for dispersing and for colonizing new areas – it’s how spiders can get to far away islands, or cleared / replanted crop fields. Tiny species can do this throughout life, but larger-bodied species only do it during their smaller juvenile stages.

This ‘Bus Of Mum’ situation is the source of some viral videos you might have seen described as ‘disco ball’ spider, or some misunderstandings about squashing spiders ‘releasing hundred of babies‘. Firstly – don’t squash spiders. Secondly – if a wolf spider female dies while she is carrying spiderlings, they will flee, and there can indeed be hundreds of them. The disco spider is a much nicer story, and happens because wolf spiders have a tapetum lucidum (reflective layer) in four of their eyes (the big front ones and a pair below), which can reflect direct light back at the observer. Swing a torch beam over a lawn at night and you may well see lots of little glittering specks – nocturnal wolf spiders on the hunt. This tapetum is present in baby wolf spiders too, so if a female is carrying lots of spiderlings, all looking around, she can be very glittery at the right angle!

We don’t have any L. tarantula native to the UK, although we do have lots of much smaller wolf spiders. You will see them a lot if you’re out and about (and looking down), running through the grass, basking on the side of plant pots or sunny rocks, and holding on tight to their papery white egg sacks. They’re harmless spiders that do a colossal amount of pest control for us.

But yeah, that life cycle toy is rubbish.

Image credits:

- “Lycosa tarantula” by Benjamin Carbuccia is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- “Lycosa tarantula 02” by Provencio.es is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

- “Lycosa Tarantula” by Alvaro is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

- By WanderingMogwai – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=121389642

Leave a comment